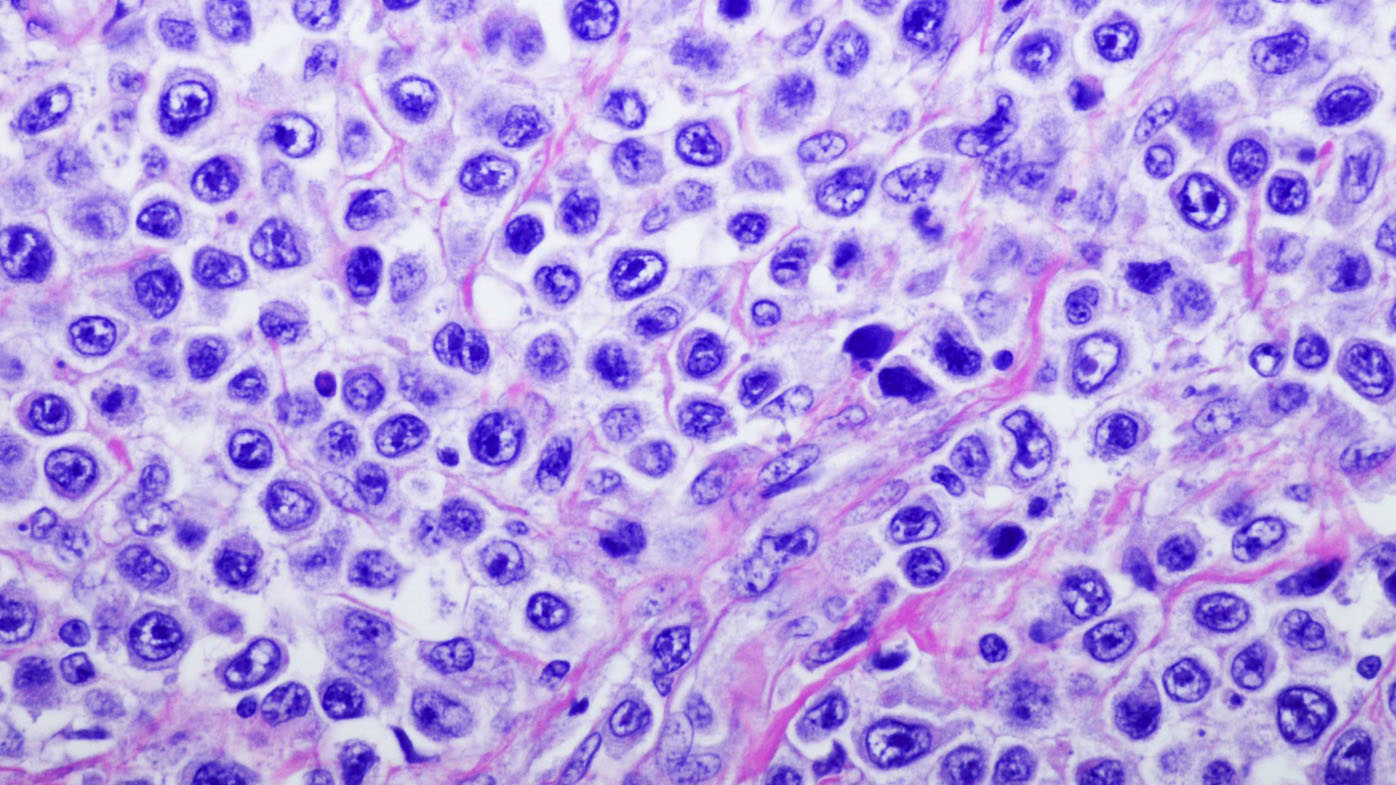

New research has helped scientists better understand the more than 60 different molecular subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), revealing just how diverse and complex this group of blood cancers is.

“From a biological standpoint, molecular lymphoma subtypes are very different from one another,” said Dr. Georg Lenz, Director of the Department of Hematology, Oncology and Pneumology at the University Hospital in Muenster, Germany. “These complexities potentially warrant different treatment approaches.”

Expanding our knowledge of these unique molecular drivers may open the door for targeted treatment approaches. Dr. Lenz expects we will learn more about these approaches during the ASH congress.

A Tale of Two Characterizations

NHL subtypes can be divided into two broad categories based on how quickly the disease progresses: they can either be indolent or aggressive. Indolent lymphomas, such as follicular lymphoma (FL), are usually slow-growing and represent up to 40 percent of all NHL cases. Aggressive lymphomas grow at a much faster rate, such as one of the most frequent subtypes, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Fast Progress in Slow-Moving NHL

The treatment landscape for indolent NHL, which includes follicular and marginal zone lymphomas, has been evolving quickly. While many patients still receive chemotherapy, targeted therapies have been making headway. At this year’s ASH Annual Meeting, Lenz expects to see more data from trials of these investigational therapies in combination with—or instead of—chemotherapy, opening the possibility for chemotherapy-free treatment.

“While we see increased interest in chemotherapy-free treatments, these approaches still have serious side effects,” Lenz said. “We still have a lot of work to do in managing these toxicities.”

Fortunately, most patients with indolent NHL respond well to treatment, but about 20 percent of FL patients relapse rather early after initiation of therapy. Since each patient responds to treatment differently, clinicians need to adapt treatment approaches accordingly, particularly for patients who do not initially respond well.

“This could be the next step for patients,” Lenz said. “It’ll be a challenge for years to come, but hopefully, we’ll see some progress in predicting treatment responses at this year’s ASH.”